I started my study of Taiji in 1970 with Professor Cheng Man-ch’ing (1902– 1975) at the T’ai-Chi Ch’uan Association at 211 Canal Street, New York City. I was then thirty-three years of age and am now eighty-three.

At that time, I had almost no idea what Taiji was. All I knew was that I was very high-strung and uncoordinated, and after my initial skepticism, Taiji appeared to be a solution to these issues.

Professor Cheng spoke and understood only Mandarin, of which I knew not even one word. So everything I asked him was translated into Mandarin, and then Professor Cheng’s answers in Mandarin were translated back into English. Professor Cheng also communicated silently, using various gestures.

One of the first things I was repeatedly told in class was to relax. In fact, “relax” was the reply to most questions my classmates and I asked.

As I learned to relax, I saw how doing so helped everything I did. I started to recognize all of the unnecessary tension I was applying to using a table saw, practicing the harpsichord, washing dishes, driving my car, and even getting out of bed in the morning.

Yang Cheng-fu

Cheng Man-ch’ing was an inner student of Yang Cheng-fu (1883–1936), who was considered to be one of the top-ten Chinese martial artists of the 20th century—quite an accomplishment considering the millions of high-level martial artists in China during that century.

In class, Professor Cheng said that relax (song) was the main word used by Yang. Here are Professor Cheng’s words to that effect:

Relax (song). My teacher must have repeated these words many times each day. “Relax! Relax! Relax completely! The whole body should completely relax!” Otherwise he said, “Not relaxed. Not relaxed. If you are not relaxed, then you are like a punching bag.”1

“If you are not relaxed, then you are like a punching bag” can perhaps be interpreted as follows: as soon as you stiffen when embroiled in a real fight with a high-level Taijiquan practitioner who is adept at using softness, that is when you will get hit.

The Meaning of Relax It took time for me to learn that relax is routinely used as an English translation for the Chinese word song. The character for song (see Fig. 1-1) includes a pine tree (lower part) and hair (upper part). The drooping branches and hair suggest letting the musculature relax to the point of having the nonexistent strength of hair. Relax, however, implies letting go totally, which is one aspect of song. But song also has a supportive aspect (suggested by the trunk of the tree). The idea is that when in a state of song, your skeleton supplies an upward support to the body even though the musculature is drooping. So when the word relax is used in Taiji, it is understood that the muscles are releasing, but the integrity and optimal alignment of the skeleton is maintained.

Fig. 1. The character for song, which is often translated into English as relax. The character includes a pine tree (lower left part) and hair (upper right part).

Attaining Song

Experiment 1-1. Stand with your feet parallel, a comfortable distance apart. Release all tension in your body. Recreate the heavy feeling you get after a hot bath—especially when you let the water drain out while you recline in the tub. Release your eyes (liquefy your eyeballs and feel them pooling in their sockets). Release your temples, nasal passages, jaw, tongue, throat, shoulders, back, arms, chest, abdomen, lower abdomen, and even your legs. Feel the heaviness of everything hanging from and supported by your skeleton. Do not let your head droop but extend its top upward without contracting your neck muscles.

The Importance of Releasing Tension in Doing Taiji Movement Stability (Root)

Another aspect of song is “root.” at is, by attaining a state of song, your center of gravity is low, and you are “rooted” to the ground similarly to a tree.

Experiment 1-2. Stand with your feet parallel, a comfortable distance apart. Release all tension in your body. Recreate the heavy feeling you get after a hot bath. Release everything mentioned in Experiment 1-1. Feel how stable you are. Then tense your chest. Feel your center of mass rise and your stability decrease.

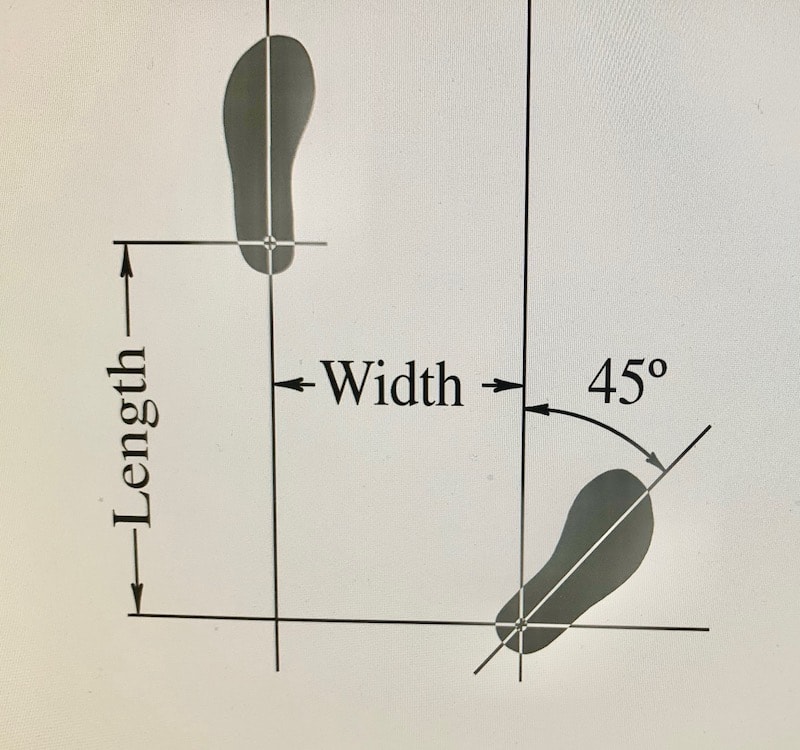

Fig. 1-2. The positioning of the feet in a 70-30 stance. The rear foot is at 45 degrees to the direction of the stance and bears 30 percent of the weight of the body. The feet are a shoulder width apart. To test this width, rotate your rear foot inward on its heel until its centerline is parallel to that of your forward foot. The separation of these two centerlines should be equal to the distance between your shoulder joints. To test the length, shift your weight 100 percent onto your rear leg, letting your forward leg slide backward until it stops. Any backward movement means that when you originally stepped into that stance, you over reached that foot and prematurely committed your weight.

Health

Professor Cheng reminded us that our distant ancestors walked on all fours, with their midsections hanging from their spines. Every step provided healthful movement of organs, glands, and other bodily tissues. The movement also promoted free flow of blood, with its transport of oxygen and nutrients into cells and waste products out. Becoming upright provided enormous developmental value. But we paid a health price by having our organs stacked one upon the other, with little freedom to move or receive nutritive and cleansing effects. Of course, there is no turning back, but by relaxing and doing healthful movement, we can mitigate some of the harmful effects.

Spirituality

Song also has a spiritual aspect. By learning to release unneeded physical ten-sion, we are paving the way for also releasing wrong thinking and the frequent overstepping of bounds of our emotional systems. However, walking that path requires sustained vigilance, critical but objective self-observation, and consistent work. Success is definitely not automatic.

Push-Hands

Experiment 1-3. Stand in a 70-30 stance (see Fig. 1-2). Have a partner push you backward. Then tense your upper body and notice how much easier it is for your partner to move you. Then release everything downward; have your partner push you again with the same strength as before and observe any increase in stability.

After a year of learning Professor Cheng’s Taiji form, I was allowed to start learning push-hands, a two-person exercise wherein each participant tries to uproot the other by using the Taiji principles. Here too, we were told not to use any strength and relax completely. The question was how it could be possible to push someone without using strength. When Professor Cheng would push a student, he always did so by first touching him or her. Whenever he pushed me, I was amazed by his wonderful precision and how little force it took for him to send me flying, but still, some strength was needed.

A Seeming Contradiction

Because I saw how much value Taiji study and practice provided, I overlooked the glaring impossibility of doing the movements by using zero strength and simply devoted myself to moving in the most relaxed manner possible.

There was, however, one unanswered question: How could I lift an arm or even move a finger without using any strength? Of course, I knew that these actions could be done more efficiently by letting go of all unnecessary strength. Yet my classmates and I were repeatedly told to do the Taiji movements without using any strength. Using no strength was an obvious impossibility, but the senior students insisted that it was possible.

I could understand the possibility that what was really meant was to reduce the amount of strength used to a bare minimum and that I should not take “use no strength” literally. But Taijiquan originated in China as a martial art hundreds of years ago and was the top martial art for a long time. The idea that Taiji training involves learning to use minimal strength seems antithetical to its martial aspect. In the words of Stanley Israel (1942–1999), an accomplished martial artist and a senior student at Professor Cheng’s school, “It is impossible for there to be a martial art that does not use some sort of strength.”

As mentioned earlier, the character for song involves a pine tree, with its strong central trunk and downward-hanging branches (Fig. 1-1). The trunk can be thought of as yang (reaching upward) and the hanging branches as yin. In the context of Taiji movement, however, the trunk can also be thought of as yin—it is supportive and rooted in the earth, with no power for producing expansive movement. Such movement was exhibited and emphasized by my later teachers, Harvey Sober and Sam Chin, and required by a martial art. So a yang counterpart to song is required in order to balance yin and yang.

- Cheng Man-ch’ing, Cheng Tzu’s irteen Treatises on T’ai Chi Ch’uan, tr. Benjamin Pang Jen Lo and Martin Inn (Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books, 1981), 88.

The above is an excerpt from Tai Chi Concepts and Experiments—Hidden Strength, Natural Movement, and Timing by Robert Chuckrow, Ph.D., publication date April 1, 2021, YMAA Publication Center, ISBN: ISBN: 978-1-59439-741-7.